The Problem

The game Super Smash Bro’s: Melee (SSBM) was released by Nintendo in 2001. SSBM is a unique fighting game that places a lot of emphasis on movement. A vibrant competitive scene emerged as early as 2003. The biggest tournaments have as many as 3000 entrants and prize pools upwards of $50,000. The top players have been playing for more than ten years as a full time job. Corporate sponsors have legitimized it even further, to the point where a large handful of people have careers in the Smash scene. They have pushed the game to the level where single frames of the game can determine the winner and loser. The game runs at 60hz, and people can consistently do techniques with two or three frames of accuracy. The game was not designed to be played like this, and thus there are some strange mechanics when it is. One of these is the issue of “back dashes”; the action of the in-game character turning around and doing a dash in that direction. Sparing the gory details — there are two ways to do this: a “smash turn” and a “tilt turn”. A smash turn will turn your character in one frame, and a tilt turn will turn your character in 4-5 frames. If the advantage of the smash turn is not already apparent — the best human reaction times are below 200ms. A difference of four frames (~67ms) could be the difference of being able to react to your opponent and guessing. Smash turns are not possible to do totally consistently, even with the best controllers, due to the way the game polls for inputs. A very small percentage of controllers have an oddity on the joystick potentiometer that causes them to be fairly consistent, but nobody can recreate it or study it since it goes away when the potentiometer is removed. Top players will spend upwards of $500 to get one of these controllers. I am confident that I can modify the controller in a way to perform smash turns consistently for less than $50.

Data Collection

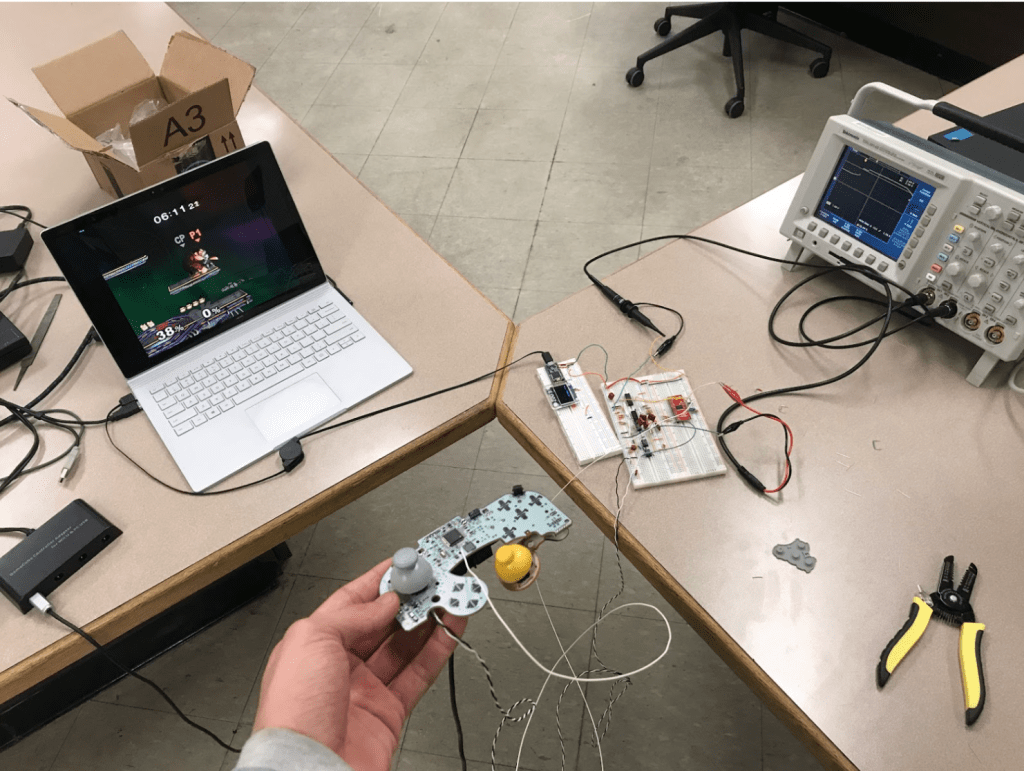

The first step to solving any problem is understanding it, so I spent a week just collecting data about how quickly it is possible to move the stick and how fast I move it in game when I am playing normally. The primary goal was to look at how fast it was possible to move the stick. Initially I just look at this on a scope taking a single sample. The time from neutral to full deflection of the stick was generally about 11-13ms for an input to the left and 13-15ms for an input to the right. Another interesting note that I found is that every stick is quite different in terms of the neutral voltage and full deflection voltages. The program needed to be calibrated every time which means that the end circuit may have to be calibrated to a specific controller unless the accuracy is not super important. After this I started reading these values with a Raspberry pi so I could use the data in python scripts in real time. With an external ADC the pi could read the analog stick values with an accuracy in the microsecond range (more than fast enough). The first program I wrote calculated the time from the tilt turn threshold (.2875 of full deflection) to the smash turn threshold (.8 of full deflection). This is the only time we really care about. An add on I did to this program was calculating a suitable RC pair (with standard R/C values) to make the cutoff frequency of a high pass Sallen Key filter around what was possible with the stick. My first intuition was that the time calculated from the program would be a period and I calculated the time constant needed from that, but after some experimentation it seems that that is not the case. I still need a reliable way to find the cutoff frequencies for the filters based on the collected data. One way to estimate this may be to extend the input to a triangle wave, and use the frequency of that. This could work because a triangle wave is comprised mostly of a sine wave with the same frequency (it is the first term in the Fourier series). An extension of a typical input is shown below. Red is the input, grey is the extended triangle wave, and blue and green show the periods of each of those respectively.

The second big program that I built was one that recorded all of the inputs for a specified amount of time and wrote them to a text file in the form:

time0,value0

time1,value1

time2,value2

…

Where the times were the system clock time that they were recorded at. A second program parsed the data and ran it through the program specified earlier for a given time period. During this time period it would return all of the deflection times in the order that they happened. In the end, it is more useful for players to calibrate the system by going as fast as they can, not by recording real matches. This is because the goal of the system is not to make back dashes easier, it’s just to make them consistent. By looking at how people already play, we are modifying the system to fit the player. The player should have to learn the system, not the other way around. All the system needs to do is be robust and have consistent behavior and feedback to the player. It was still useful to look at the data from real games, however, because players have a lot of fast inputs, and most of them are not actually meant to be back dashes. Additionally, the difference between how fast people already move the stick and how fast they can move it is not very big. The fastest deflection times I could hit consistently were ~4ms-5ms. In game it was fairly common to hit deflection times of 6ms or below. This should not be a big deal because 1.) any time you are moving the stick fast, even if it isn’t for a back dash, it will not be harmful to quantize the signal. In fact, it will he

lp. 2.) The filters will have some cutoff slope that should make this okay.

Lastly, I coded a python script to generate suitable R and C values based on the readings of a players input speed.

The Solution

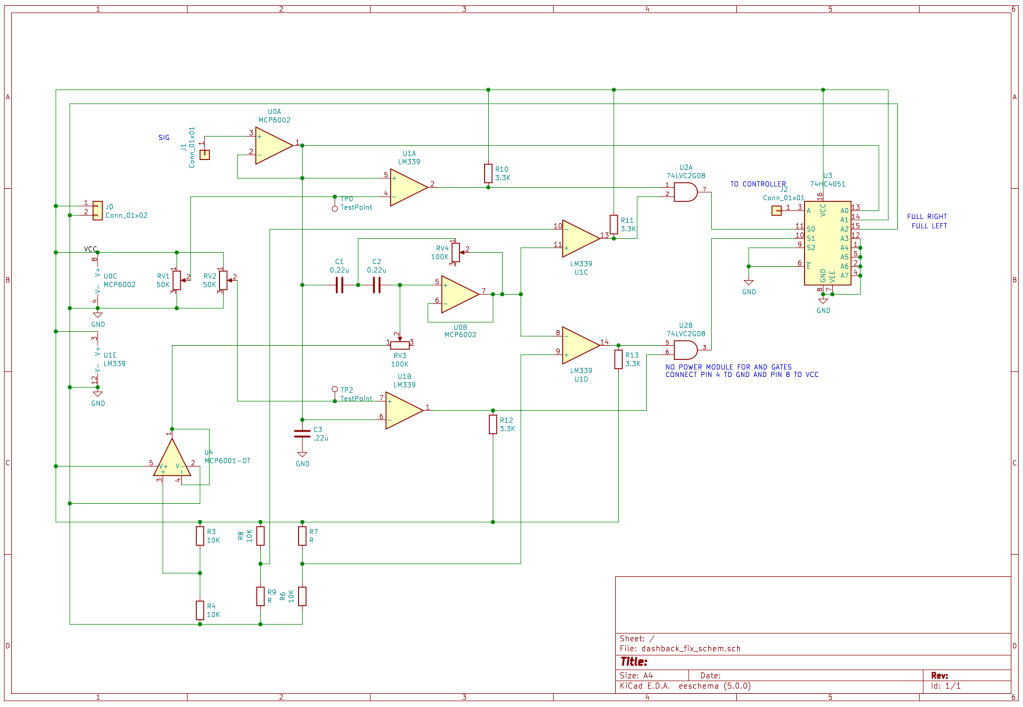

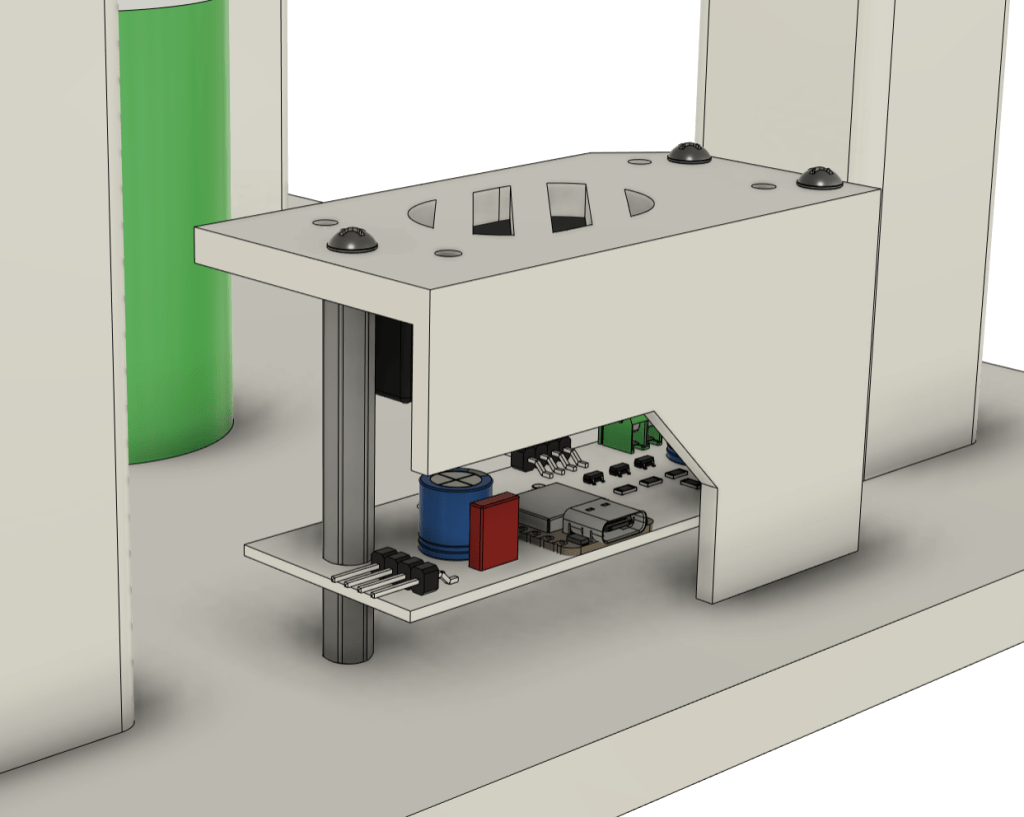

Schematics and Board Layout